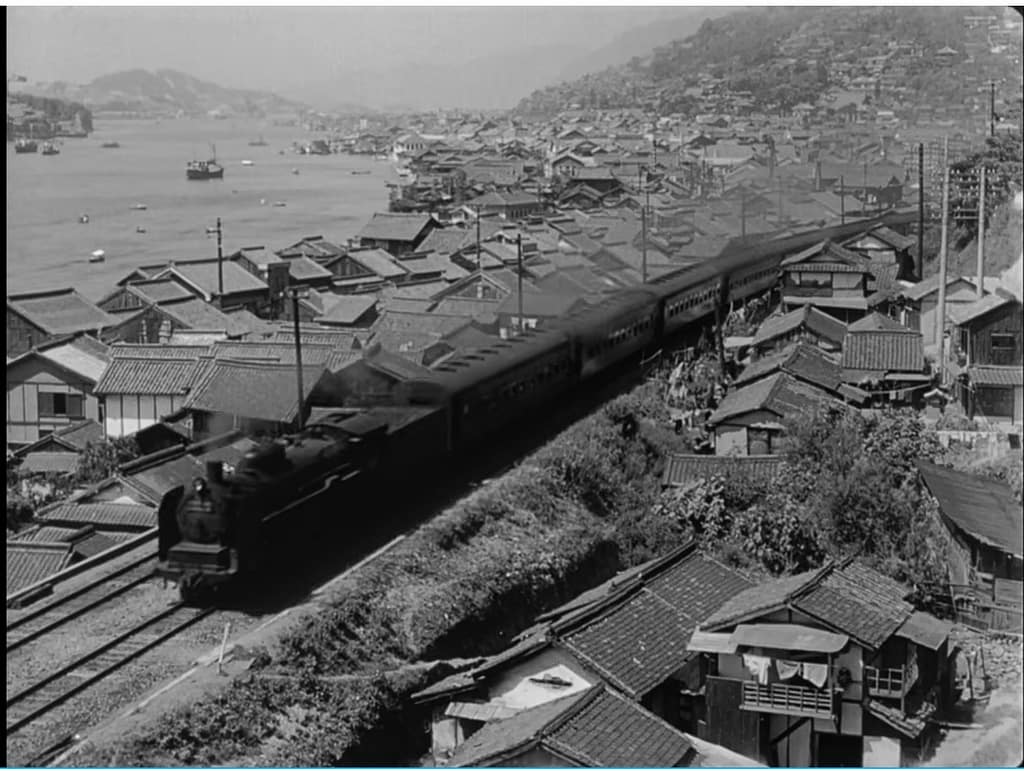

昭和时期(1926年至1989年)恰逢日本现代化的进程。在这一时期,日本人经历了西方现代文明对本土的强烈冲击,社会思想在动荡中经历了巨大的变迁。我观看过的电视剧《阿信的故事》以及宫崎骏的动画电影《起风了》,都给我留下了深刻的印象。以至于现在,每当我看到一位在这个时期成长起来的科学家,我都能想象到他在年轻时代是如何在各种社会思潮的包围中确立自己的研究志向,并克服现实中的种种困难的。战后重建时期的日本,处于昭和时代的中后期,其科学研究水平也是在这段时期显现出来的。我之所以跟“昭和”年号联系起来,是因为这一时期发表的日文论文中的年份是用“昭和二十六年”这种年号纪年法的。你每查到一篇论文,都需要被迫去查算到底这是公元多少年。从汤川秀树获得诺贝尔奖(1949年)开始,日本不断出现在理论物理进程中作出了无法绕过的里程碑式工作的物理学家。诺贝尔奖得主绝不是孤立存在的。能出现若干位诺贝尔奖得主,就说明在更多的分支领域当中,也出现了大量奠基式的人物和工作,这也表明整个科学研究界的文化环境是良性的,土壤是肥沃的。

在我的小领域中,昭和时代成长起来的日本科学家还有好多位。上一篇文章“感字”提到的荻野一善就经常与日本流变学先行者中川鹤太郎共同发表论文。同为溶胀网络的重要研究者之一——小贯明事实上是与川崎恭治一道进行相变研究的,后者是临界现象的模式耦合理论创立者。日本在非平衡统计物理的更早和重要的人物就是大家熟知的久保亮五(就是Green-Kubo关系中的Kubo)和森肇(就是Zwanzig-Mori投影算符中的Mori)了。

我博士导师的博士导师——藤田博(,是昭和十九年(1944年)京都大学理学部物理学科毕业,该年B-29开始空袭东京。而一年之后的1945年就是日本在遭遇两颗原子弹爆炸之后,对内全国玉音放送《终战诏书》,对外宣布无条件投降。1946年日本天皇发表《人间宣言》,自己说明自己并非神,《日本国宪法》公布并在次年(1947)年施行。

也就在这一年,藤田到京都大学的水产科工作。虽然他对微分方程感兴趣,但不得不应用于渔业,因此发表过一些以《産卵過程に対する密度効果の形式について(论种群密度对产卵过程影响的形式)》为标题,实际内容是一个简单的动理学方程的高斯分布解的论文[1]。

藤田在1954年到威斯康星大学化学系做博后。正是在这段时期他作出了超离心理论和方法上的代表性工作。当时在威斯康星大学化学系的教授John Warren Williams(1898~1988)(他本人不喜欢John这个名字,他和他身边的人称他Jack Williams)由于Svedberg1923年曾造访威斯康星大学而对超离心方法感兴趣。1934~35年Jack到Svedberg那里学习大约一年的超离心技术。回美国后主导了美国第一台超离心机的落地,就在他自己的实验室,并且用于蛋白质研究。Williams实验室因此也成为了美国趣离心方法研究的代表性实验室。藤田博来做博后之后,发挥了他在求解扩散方程方面的特长,解决了长期存在的问题,即考虑扩散系数和沉降系数的浓度依赖性之后,它们对溶质沉降边界区域形状的定量影响。他后来写的书Mathematical Theory of Sedimentation Analysis(Academic Press 1962)是超离心基础理论领域的重要著作,但可能更多人会知道他写的Foudations of Ultracentrifugal Analysis(John Wiley & Sons 1975)。在前一本书中我们可以留意到,藤田并非一位对解方程感兴趣的数学家,而是一位物理学家,因为他把自己所关注的扩散问题归类为“不可逆热力学”。这也是物理学界新形成的领域,这可大约以de Groot的著作Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processe(North-Holland 1952)和普里高津的著作Introduction to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processe(Charles C Thomas 1955)为标志。

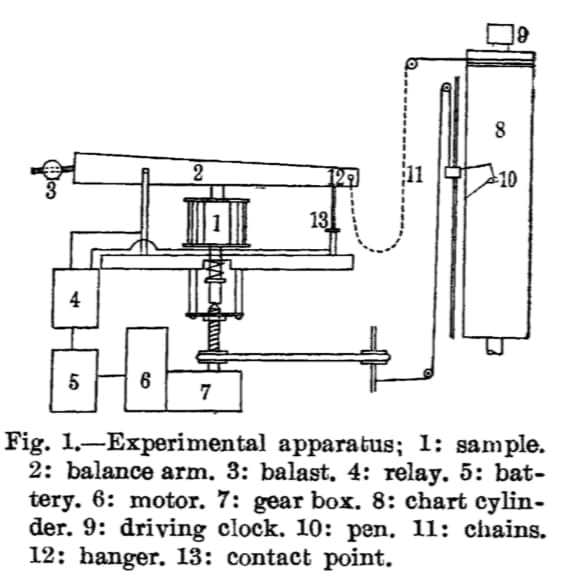

尽管藤田是一个擅长理论的人,但是他可能也搭过实验仪器。在这篇1952年的论文里[2](应该在他去美国之前),他改装了更早几年报道在J. Appl. Phys.上的[3]一种对软体进行压缩形变的力学测试装置。用于测量浓到像凝胶状的高分子溶液的弹性模量。我上一篇文章提到的荻野的论文,就是借用藤田改进的仪器进行实验的。

“流体的弹性”或“流动的固体”,是流变学的核心问题。《流动的固体》作者中川鹤太郎在同时代就已经发表了多篇关于液体的粘弹性的论文(值得注意的是,中川称“rheology”为“流动学”,因此中文的“流变学”并不来自日语)。《流动的固体》书中所称的久山多美男关于“粘弹性系数的新测量方法”(亦称久山先生可能是在日语中道次使用“粘弹性”),就被中川改进并于同年(昭和26年)发表于《日本化学杂志》。我在流动的固体2021中介绍过了。藤田注意到中川的研究是不奇怪的。他后来在日本的《高分子》(Kobunshi,是1952年创刊的)杂志上发表过一篇散文(1983年,这时日本的杂志早已使用公元纪年),提到他作为物理学背景的学生,刚开始学习高分子时这一交叉学科的困难在于当时还没有统一连贯的教科书或专著。确实,他在1957年就与岸本昭一同在《高分子》发表了一篇有趣的3人对谈,对谈内容是围绕当时在橡胶长时间应力松弛行为中区分物理上的松弛和由于化学老化造成的松弛。开头3人就关于“化学松弛”、“物理缓合”等术语如何翻译成日语抱怨了一番,最终大家打算找一家coffee shop进行“精神缓和”(mental relaxation)。

因此可能说藤田博(我师爷)关于高分子方面的研究,最早就是从流变学开始的。

References

- H. Fujita, "Factors affecting the type of population density effect upon average rate of oviposition", Population Ecology, vol. 2, pp. 1-7, 1953. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02789688

- H. Fujita, K. Ninomiya, and T. Homma, "Mechanical Properties of Concentrated Hydrogels of Agar-agar. I. Modulus of Elasticity in Compression", Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, vol. 25, pp. 374-378, 1952. http://dx.doi.org/10.1246/bcsj.25.374

- S.L. Dart, and E. Guth, "Elastic Properties of Cork. I. Stress Relaxation of Compressed Cork", Journal of Applied Physics, vol. 17, pp. 314-318, 1946. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1707719